hiliun

Oct 7, 2010

Writing Feedback / Formal Analysis of Monet's "The Scene at Giverny" [2]

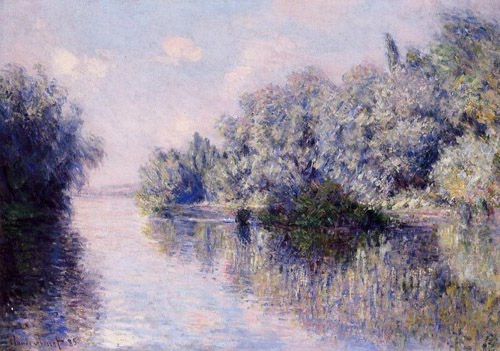

The scene at Giverny (1885) by Claude Monet

25 1/2 x 36 1/2 in.

Oil on canvas

Viewed at Museum of Art Rhode Island School of Design (September 28, 2010)

A painting is assumed to be viewed with eyes. It is nonsense to say looking at a painting with one's ears, nose or mouth. However, The Scene at Giverny(1885), an oil work on canvas by Claude Monet, certainly challenges this "common sense". As the name suggests, The Scene at Giverny, with a medium size of 25 1/2 by 36 1/2inches, is a view of the bank of the Seine River in the early morning. Rather than simply depicting the actual shape and color of the landscape in the painting, Monet conveys his strong and constant interest in the effect, or the impression, produced by the object's surrounding environment, lights, smokes as well as air. The viewer can, as Monet did, grasp the beauty of Giverny from the aspects of content and composition, color and light, and texture and technique.

To the viewer at a hastily glimpse, The Scene at Giverny might look more like two large fluffy blue-violet pompons placed on a milky cotton cloth in the light fog, a scene delivering the senses of softness and comfort. Then the fog lifts from the painting at a second look. There are two small islands covered with lush plants on each side of the painting and the bending waterway rests in the middle. It might be a sunny day with some pleasurable clouds, which delay the evaporation of those lovely dews on leaves and petals by the contact of the first beam of sunlight and keep the freshness of a delight morning. The surface of water is tranquil with few ripples probably aroused by the breeze or the ditty of an early bird. It is interesting to find that the trees and their reflections in the water on each island form two converging triangles from each side of the painting pointing to the horizon. This specific shape actually directs the viewer's eyes to the turn of the river where the water and sky have an intercourse. However, the focal point of the painting is in fact the lightest and most vague part of the whole painting. Though it's quite a narrow view of the riverbank in the painting, the placement with the relative darkness of the two islands on each side of the shining river surprisingly instills in the viewer a feeling of infinity, extension, and broadness of the prospect of the waterway and the openness of the sky.

Monet is such a colorist, whose use of colors and lights wakes up every sense of the viewer to feel the painting. Since the work is done in 1885, after the Industrial Revolution took place which tremendously aggrandizes the amount of colors painters can apply to their painting while decreasing the prices to make an easier access to the once expensive pigments, the viewer can see, though not obvious at the first sight, a lot of pure light colors--blue, green, pink and violet-- with little variations. The hue of the painting is airy and gentle: the baby blue sky, soft pale pink clouds, and gray cyan-blue, green, and lavender leaves with their equally hazy reflections in the water. For there are little warm colors like red, salmon, or orange, the colors, almost in the same saturation, are generally cool with little contrasts. Monet also puts more light on right side by depicting it with more details and brighter colors while making the left side relatively darker and colder. The capture and placement of lights directs the viewer's eyes from left to right while delivering a sense of airflow motion at the same time. The viewer, who might at beginning be mesmerized by the painting's overall fantastic, delicious atmosphere, will be enraptured after closer study by its exquisite and subtle yet murky complexion of lights and shadows whirling on the trees and waters and even smell the moisture and freshness of a chilling dawn as Monet did.

By stepping closer, the viewer will observe another important signature of Monet as an impressionist, the heavy impasto, which is in itself a delight. The glorious texture of small stroke in all different directions depicts the sumptuous richness of the color gradation and the diversification of light fluctuation, but it may also suggests a fast yet confident brushwork that could implies, when considering its size, which is a little bit smaller than the common size of Monet's landscape paintings., that the painting is but a study work of the Giverny scenery for Monet. Although Monet applies a thick impasto to his work, there's barely a clear line or border of his objects: the viewer can't truly identify the interval of the trees, the shape of the clouds, or even the boundary of sky and water, which seems to be more like a transparent fluid as a whole part rather than two intersecting mediums. The water, sky, and air are treated as combined, influencing, attracting, and interpenetrating one another. However, there's an inexplicit pleasure for the viewer to try to discern what is in the painting by examining the light-and-dark relationship and the vague form of each single color. In fact, such vagueness precisely captures the movement of trees, the flowing lights, and the dancing winds in a most elegant and romantic way.

Claude Monet presents us in The Scene at Giverny a romantic wonderland, a fairylike secret garden with his palpitating light and glowing colors, which vividly transforms a certain landscape to a more illusory reflection which does not only have the shape (though in a vague way) and the color of the original object, but also instills a overflowing sense of life and animation into it. With his sensitive visual observation, he provides us a world-wide pleasure, a simple but utmost pleasure, which rinses our mind and evokes every possible senses we possess to touch the lightness, to feel the lavishness, and to imagine the romance. All the elements such as the light, air, and wind, which have no real substances and are often overlooked by even the painters, are colorized, materialized, and vitalized by Monet. The Scene of Giverny reflects Monet's ideal of beauty, which is not defined by the subject itself as a passive object, but as an organic part to its surroundings.

Thank you for your comments and advice!!

The scene at Giverny (1885) by Claude Monet

25 1/2 x 36 1/2 in.

Oil on canvas

Viewed at Museum of Art Rhode Island School of Design (September 28, 2010)

A painting is assumed to be viewed with eyes. It is nonsense to say looking at a painting with one's ears, nose or mouth. However, The Scene at Giverny(1885), an oil work on canvas by Claude Monet, certainly challenges this "common sense". As the name suggests, The Scene at Giverny, with a medium size of 25 1/2 by 36 1/2inches, is a view of the bank of the Seine River in the early morning. Rather than simply depicting the actual shape and color of the landscape in the painting, Monet conveys his strong and constant interest in the effect, or the impression, produced by the object's surrounding environment, lights, smokes as well as air. The viewer can, as Monet did, grasp the beauty of Giverny from the aspects of content and composition, color and light, and texture and technique.

To the viewer at a hastily glimpse, The Scene at Giverny might look more like two large fluffy blue-violet pompons placed on a milky cotton cloth in the light fog, a scene delivering the senses of softness and comfort. Then the fog lifts from the painting at a second look. There are two small islands covered with lush plants on each side of the painting and the bending waterway rests in the middle. It might be a sunny day with some pleasurable clouds, which delay the evaporation of those lovely dews on leaves and petals by the contact of the first beam of sunlight and keep the freshness of a delight morning. The surface of water is tranquil with few ripples probably aroused by the breeze or the ditty of an early bird. It is interesting to find that the trees and their reflections in the water on each island form two converging triangles from each side of the painting pointing to the horizon. This specific shape actually directs the viewer's eyes to the turn of the river where the water and sky have an intercourse. However, the focal point of the painting is in fact the lightest and most vague part of the whole painting. Though it's quite a narrow view of the riverbank in the painting, the placement with the relative darkness of the two islands on each side of the shining river surprisingly instills in the viewer a feeling of infinity, extension, and broadness of the prospect of the waterway and the openness of the sky.

Monet is such a colorist, whose use of colors and lights wakes up every sense of the viewer to feel the painting. Since the work is done in 1885, after the Industrial Revolution took place which tremendously aggrandizes the amount of colors painters can apply to their painting while decreasing the prices to make an easier access to the once expensive pigments, the viewer can see, though not obvious at the first sight, a lot of pure light colors--blue, green, pink and violet-- with little variations. The hue of the painting is airy and gentle: the baby blue sky, soft pale pink clouds, and gray cyan-blue, green, and lavender leaves with their equally hazy reflections in the water. For there are little warm colors like red, salmon, or orange, the colors, almost in the same saturation, are generally cool with little contrasts. Monet also puts more light on right side by depicting it with more details and brighter colors while making the left side relatively darker and colder. The capture and placement of lights directs the viewer's eyes from left to right while delivering a sense of airflow motion at the same time. The viewer, who might at beginning be mesmerized by the painting's overall fantastic, delicious atmosphere, will be enraptured after closer study by its exquisite and subtle yet murky complexion of lights and shadows whirling on the trees and waters and even smell the moisture and freshness of a chilling dawn as Monet did.

By stepping closer, the viewer will observe another important signature of Monet as an impressionist, the heavy impasto, which is in itself a delight. The glorious texture of small stroke in all different directions depicts the sumptuous richness of the color gradation and the diversification of light fluctuation, but it may also suggests a fast yet confident brushwork that could implies, when considering its size, which is a little bit smaller than the common size of Monet's landscape paintings., that the painting is but a study work of the Giverny scenery for Monet. Although Monet applies a thick impasto to his work, there's barely a clear line or border of his objects: the viewer can't truly identify the interval of the trees, the shape of the clouds, or even the boundary of sky and water, which seems to be more like a transparent fluid as a whole part rather than two intersecting mediums. The water, sky, and air are treated as combined, influencing, attracting, and interpenetrating one another. However, there's an inexplicit pleasure for the viewer to try to discern what is in the painting by examining the light-and-dark relationship and the vague form of each single color. In fact, such vagueness precisely captures the movement of trees, the flowing lights, and the dancing winds in a most elegant and romantic way.

Claude Monet presents us in The Scene at Giverny a romantic wonderland, a fairylike secret garden with his palpitating light and glowing colors, which vividly transforms a certain landscape to a more illusory reflection which does not only have the shape (though in a vague way) and the color of the original object, but also instills a overflowing sense of life and animation into it. With his sensitive visual observation, he provides us a world-wide pleasure, a simple but utmost pleasure, which rinses our mind and evokes every possible senses we possess to touch the lightness, to feel the lavishness, and to imagine the romance. All the elements such as the light, air, and wind, which have no real substances and are often overlooked by even the painters, are colorized, materialized, and vitalized by Monet. The Scene of Giverny reflects Monet's ideal of beauty, which is not defined by the subject itself as a passive object, but as an organic part to its surroundings.

Thank you for your comments and advice!!

The painting